Battle Study Package: First Manassas

Battle Study Package: First Manassas

The First Major Battle of the American Civil War

HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE

The Battle of First Manassas (otherwise known as the First Battle of Bull Run) was the first major battle in the American Civil War. The battle eroded any optimism that the war would be a quick, bloodless affair—demonstrating that it would take a significant amount of time, materials, money, and men for the Federal Government to force the Southern Confederacy to return to the Union.

TACTICAL IMPORTANCE

Following the Confederate barrage on Fort Sumter on 12-13 April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln called forth 75,000 volunteers to crush the Confederacy, resulting in an additional four states seceding. By July of that year, two Confederate armies—Gen PGT Beauregard’s Army of the Potomac located near Manassas Junction and Gen Joseph Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah in the northern region of the Shenandoah Valley—threatened the Federal capital at Washington, DC. Opposed to these two armies were Gen Robert Patterson’s Army of the Shenandoah located in the Shenandoah Valley and Gen Irvin McDowell’s Army of Northeastern Virginia positioned around Washington, DC. Knowing the short enlistment term of his men was about to run out, President Lincoln ordered Gen McDowell to march his largely untrained army toward Richmond.

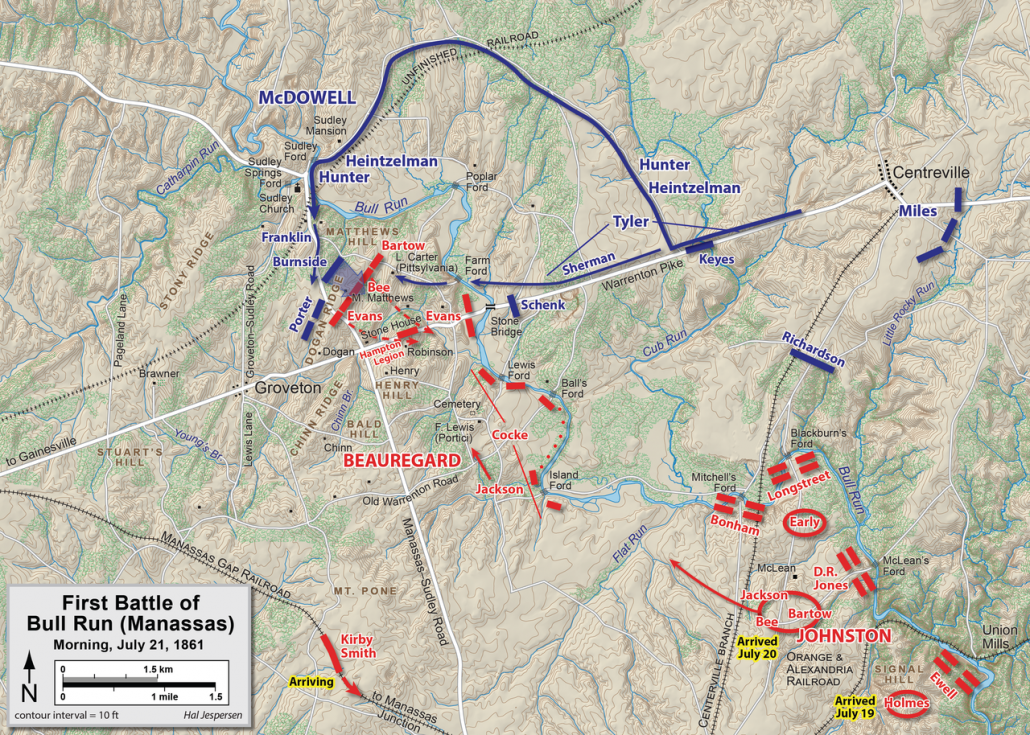

The Confederate Army of the Potomac assumed a defensive position south of the Bull Run Creek near Manassas Junction, where Gen Beauregard spread his forces to cover the multiple crossing points. Realizing that the advancing Union army greatly outnumbered his own, on the morning of the 18th, Gen Beauregard requested that Gen Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah join forces via rail at the Manassas line. Later that day, the advance column of the Army of Northeastern Virginia skirmished against Confederate defenses near Blackburn’s Ford.

By using a successful cavalry screen, Gen Johnston’s army was able to elude Gen Patterson’s forces undetected and—in the first major strategic use of railroads in military history—successfully begin reinforcing Gen Beauregard over the next few days. Following the skirmish at Blackburn’s Ford, Gen McDowell concentrated his forces around Centreville for several days while he devised his plan. With the Confederates well positioned along the fords south of Centerville as well as west behind Stone Bridge on the Warrenton Turnpike, Gen McDowell decided to launch a feint on Stone Bridge while sending two of his divisions north to cross Bull Run Creek at Sudley Ford to outflank the Confederate left flank.

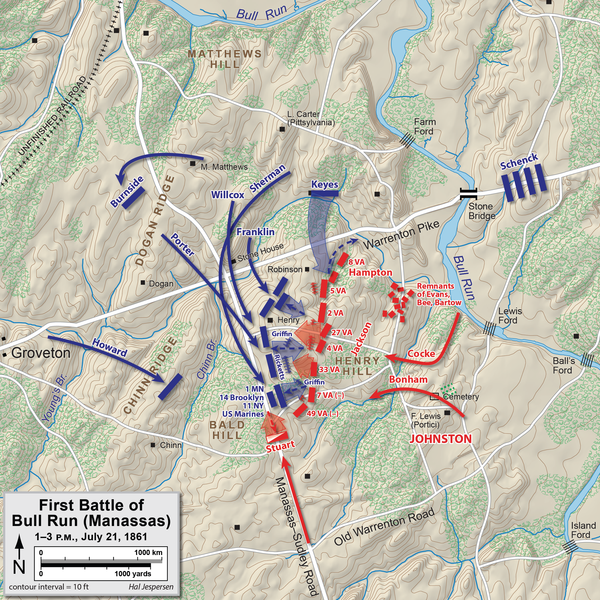

Although the flanking movement began early in the morning, the advance was delayed by inexperienced officers and the rough conditions of the flanking route. The flanking units did not begin crossing Sudley Ford until around 9:30 in the morning while the demonstration at Stone Bridge had been ongoing since 6:00. In the midst of the feint on Stone Bridge, a Confederate signal officer noticed the Union flanking column advancing from Sudley Ford and promptly notified the commander of the Confederate brigade defending Stone Bridge—Col Nathan Evans—that his flank was turned. Col Evans left a small holding force and promptly redeployed the majority of his force to Matthews Hill to stall the Union advance. Although the Confederates on Matthews Hill were reinforced by two additional brigades, by 11:30 the Union had managed to outflank the Confederates defending Stone Bridge and the weight of their numbers drove the Confederate troops back toward Henry House Hill.

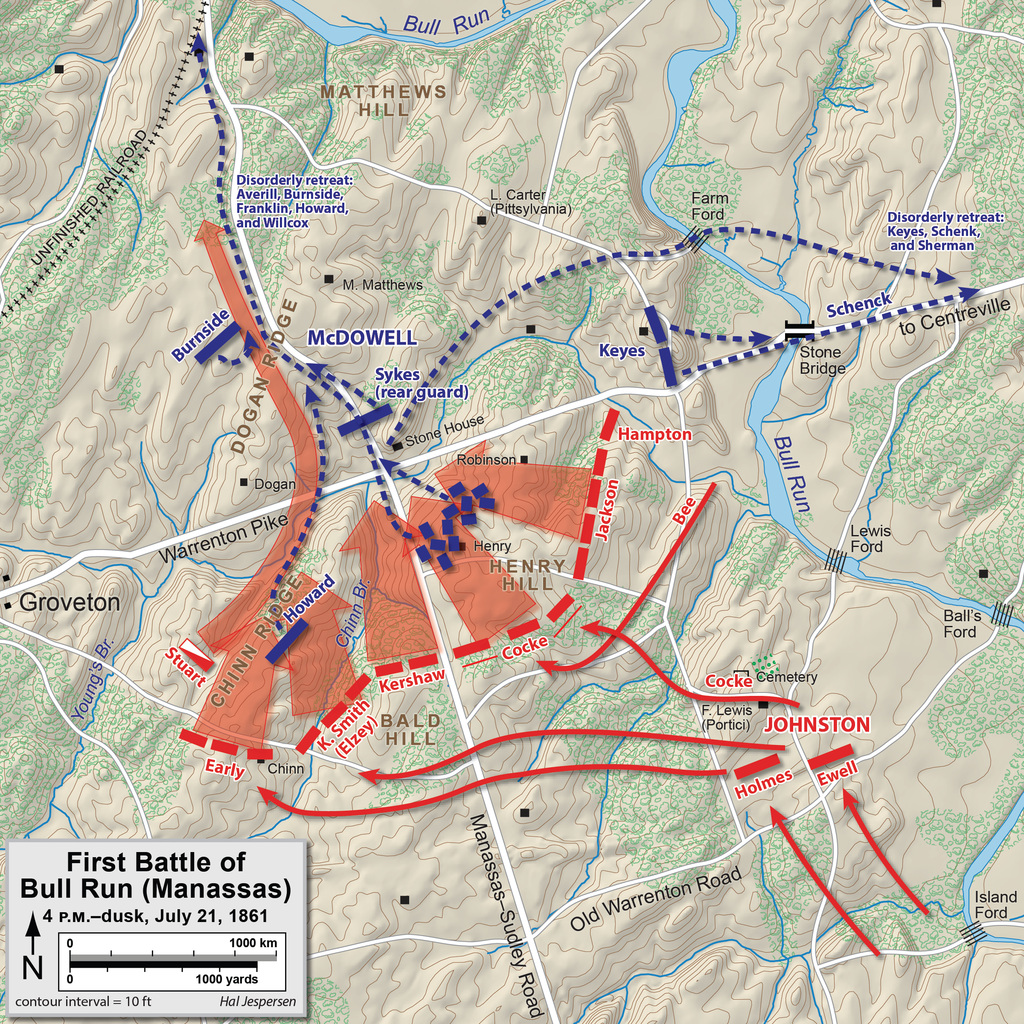

Despite this initial success, Gen McDowell stalled his pursuit to bring up his artillery and fire upon the Confederate reorganizing on Henry House Hill. However, another Confederate brigade, commanded by Gen Thomas Jackson with supporting artillery batteries, formed a defensive line past the crest of the hill which sheltered them from the enemy artillery fire and allowed them to bring superior firepower upon the advancing enemy. Gen McDowell launched a half-hearted, piecemeal effort to take Henry House Hill, eventually moving some of his artillery forward to support the infantry. However, this brought them within range of Confederate infantry and artillery—beginning a back-and-forth battle for control over the Union cannons. Union efforts to outflank the Confederate left on Henry House Hill were checked by further Confederate reinforcements. By around 4:00 in the afternoon, the Union attacks began to waiver and a successful Confederate counterattack succeeded in routing the Army of Northeastern Virginia from the field of battle. In the confusion, many Union soldiers were captured. The Confederates, however, failed to properly follow through on their victory, and the Union army managed to chaotically retreat to Washington, DC. In all, the Union forces suffered over 2,800 casualties compared to around 1,900 Confederates.

STRATEGIC IMPACT

In defeating the Army of Virginia at the First Battle of Bull Run, the Confederates seized the initiative from the Union—forcing the beaten and demoralized forces to retreat and reorganize within the defenses of Washington, DC. The Confederate forces—suffering from their own manpower and supply shortages—failed to capitalize on their victory and instead assumed a defensive position in Northern Virginia. Nonetheless, by stalling the initial Federal advance on Richmond, the Confederates prevented any further major incursion on their capital for the remainder of the year.

Maps

Study Guide

Podcasts

Books

Videos

Testimonials

“We faced them on the left of the battery, and when fifty yards from it, our men fell like hailstones.”

-Private William Barrett (USMC)

“I beheld a perfect avalanche pouring down the road immediately behind me.”

-Congressman Elihu Washburne describing the Union retreat