New Mexico Campaign

New Mexico Campaign

Historical Significance

While not as large compared to many of the American Civil War’s campaigns, the New Mexico Campaign preserved the United States government’s control over its southwest territories while denying the Confederacy an opportunity to create another theatre of war.

Tactical Importance

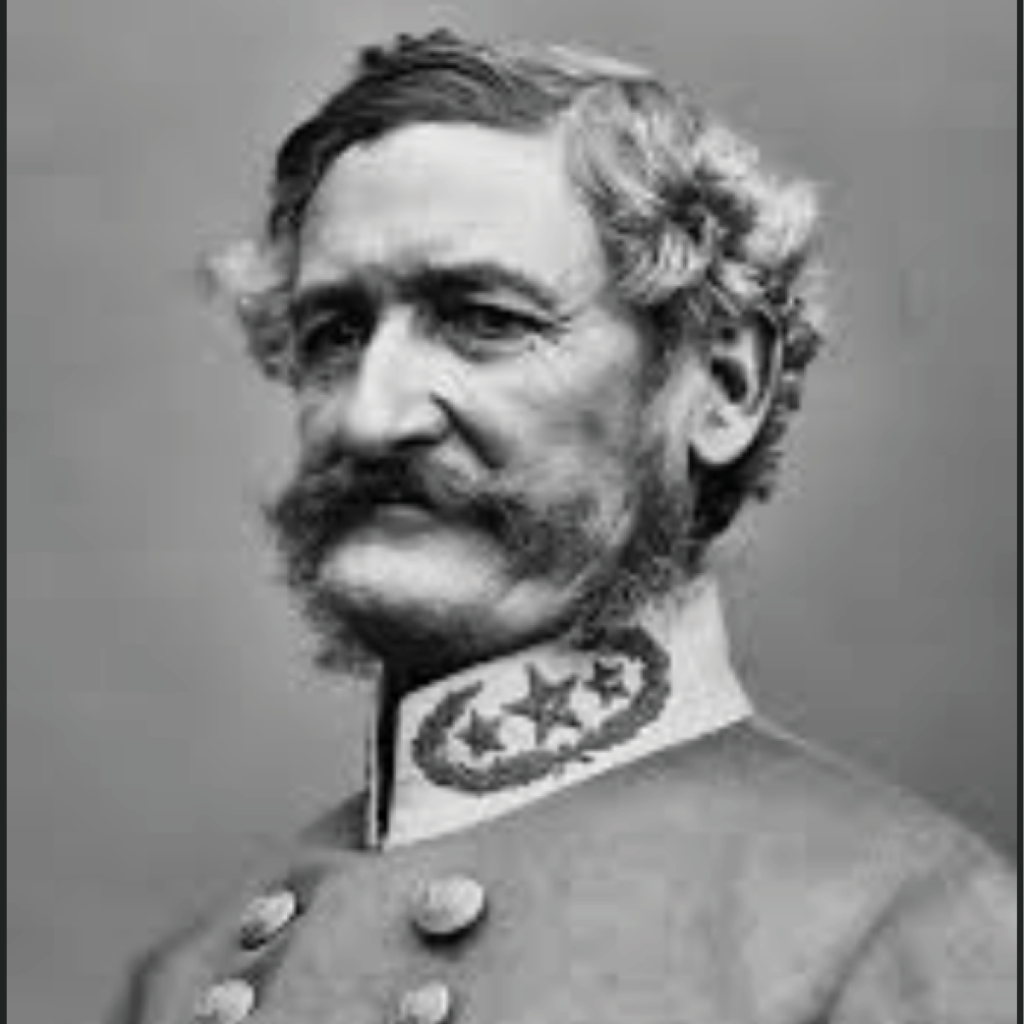

In November 1861, the Confederate Army of New Mexico, which consisted of around 2,500 men and was commanded by Gen Henry Sibley, departed northward from San Antonio in the direction of Santa Fe. By mid-February, the Confederate forces arrived near Fort Craig, which was occupied by 3,800 Union soldiers commanded by Col Edward Canby. Not wanting to leave this force behind him, Gen Sibley sought to draw the Union forces into open battle. On 19 February, Gen Sibley attempted to draw the Union into battle, but after a brief skirmish, the Federals remained behind their fortifications.

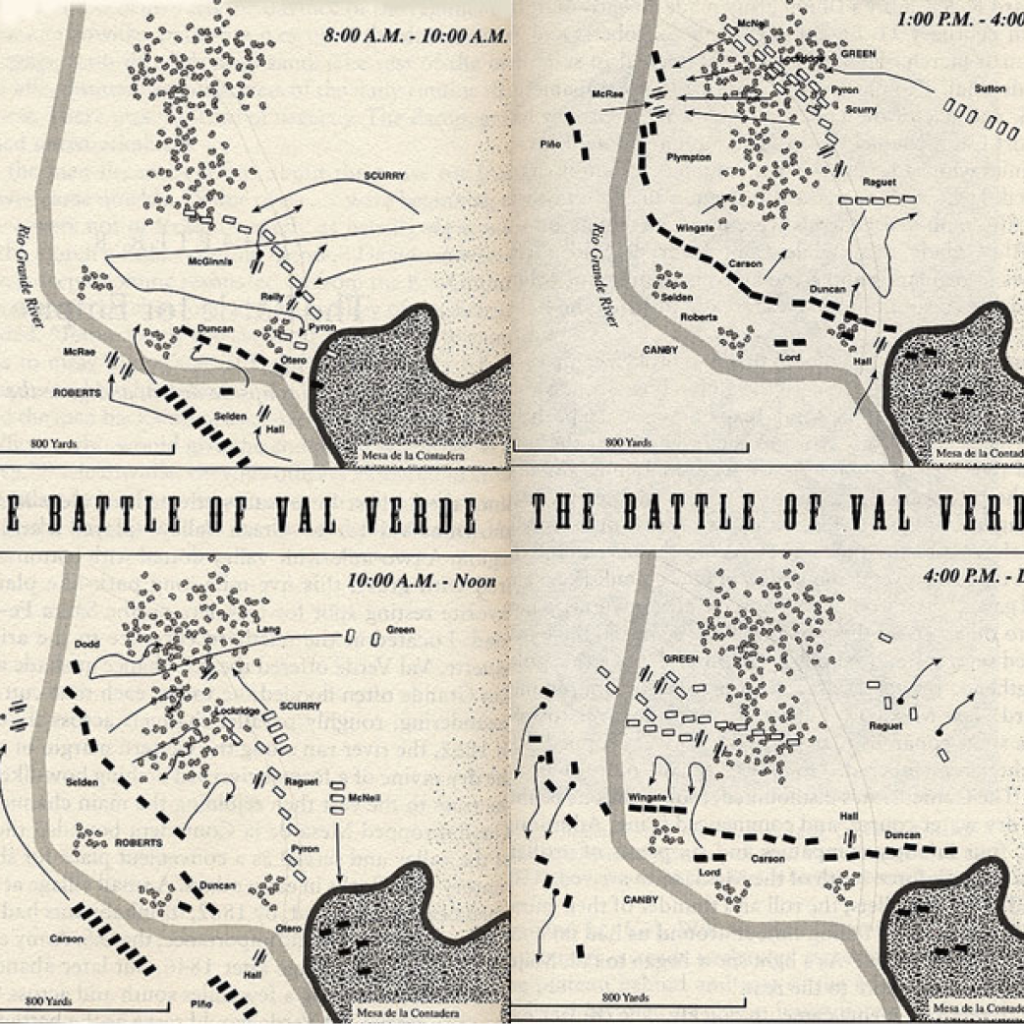

Gen Sibley then decided to outflank Fort Craig to sever the Union defenders’ line of communication. However, Col Canby followed Gen Sibley’s army and intercepted the Confederates six miles north of Fort Craig at Valverde Ford. Using the river to their advantage, Canby’s force checked the initial Confederate advance; however, Gen Sibley’s army pulled back to a bend in the river, providing the Confederates with a strong defensive position. At this point in the battle, Gen Sibley—who was ill at the time—relinquished command to Col Thomas Green, who then order Texan lancer cavalry to attack the advancing Federals. In what would be the only mounted lancer charge of the war, the Confederates were repulsed with heavy casualties. As the Federals advanced, Col Canby determined that the Confederate’s position was too strong to launch a frontal assault and began to shift his forces to assault the enemy’s left flank. However, while reorganizing their assault, the Confederates launched a determined counterattack which forced the Union forces to retreat to Fort Craig. The Battle of Valverde Ford resulted in less than 200 Confederate casualties compared to the over 400 suffered by the Federals.

Despite winning the Battle of Valverde Ford, the Confederate Army of New Mexico lost many of their horses and transportation to the enemy, which significantly slowed their advance. By mid-March, the Confederates had captured both Albuquerque (2 March) and Santa Fe (13 March); however, their slow pace allowed the Union forces to either destroy or remove valuable supplies while reinforcements—commanded by Col John Slough—arrived from Colorado. On 26 March, lead elements of Col Slough’s force ran into Gen Sibley’s army near Apache Canyon, and after a brief skirmish, both sides retired. On 28 March, the Confederates advanced against the Union forces near Glorieta Pass and after a fierce fight pushed Col Slough’s men back to Pigeon’s Ranch—where they made a determined defense before finally retreating from the battlefield. While this fight was occurring, unbeknownst to the Confederates, a small contingent of Union soldiers located their supply train at Johnson’s Ranch, which was summarily destroyed. Casualties for the Battle of Glorieta Pass were almost 150 Federals and over 200 Confederates. Without their supply train, the Confederates were forced to make an arduous retreat back to Texas while constantly hampered by a lack of supplies, transportation, and numerous small skirmishes.

Strategic Impact

The Confederate goal for the New Mexico Campaign was to open a new front to the west in order to sever Federal supply lines with the western states and territories, maintain control over the American Southwest, and potentially divert Federal resources away from more prominent theatres of war. Unfortunately for the Confederates, their inability to maintain a rapid advance in a resource-scarce region hindered their ability to maintain a long-term campaign. After losing their supply train in the battle of Glorieta Pass, the Confederates had no option but to end their territorial aspirations for the Southwest. Consequently, the initiative in the Southwest Theatre was turned to the Federals, and the Confederates would never again try to pursue offensive operations into New Mexico.

Maps

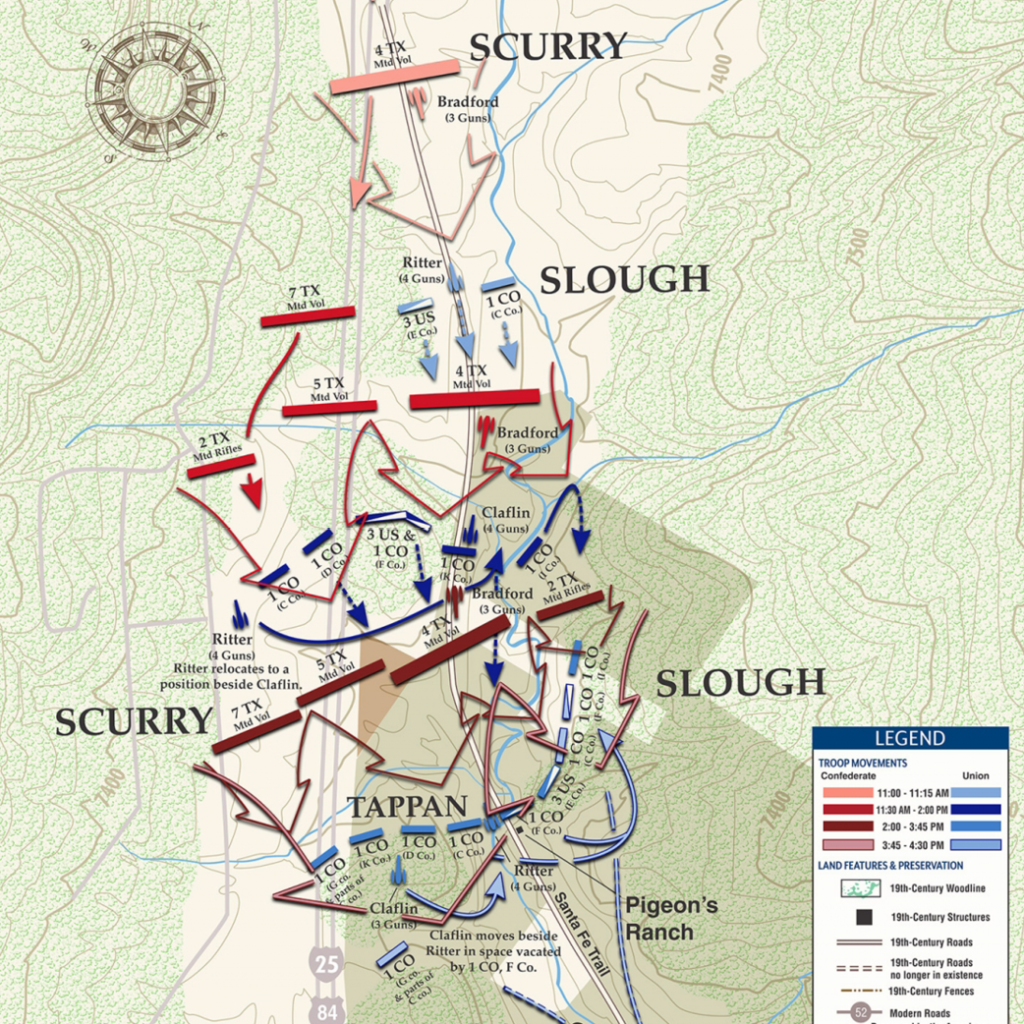

Glorieta, N.M.

March 26-28, 1862

March 28 – Pigeon’s Ranch

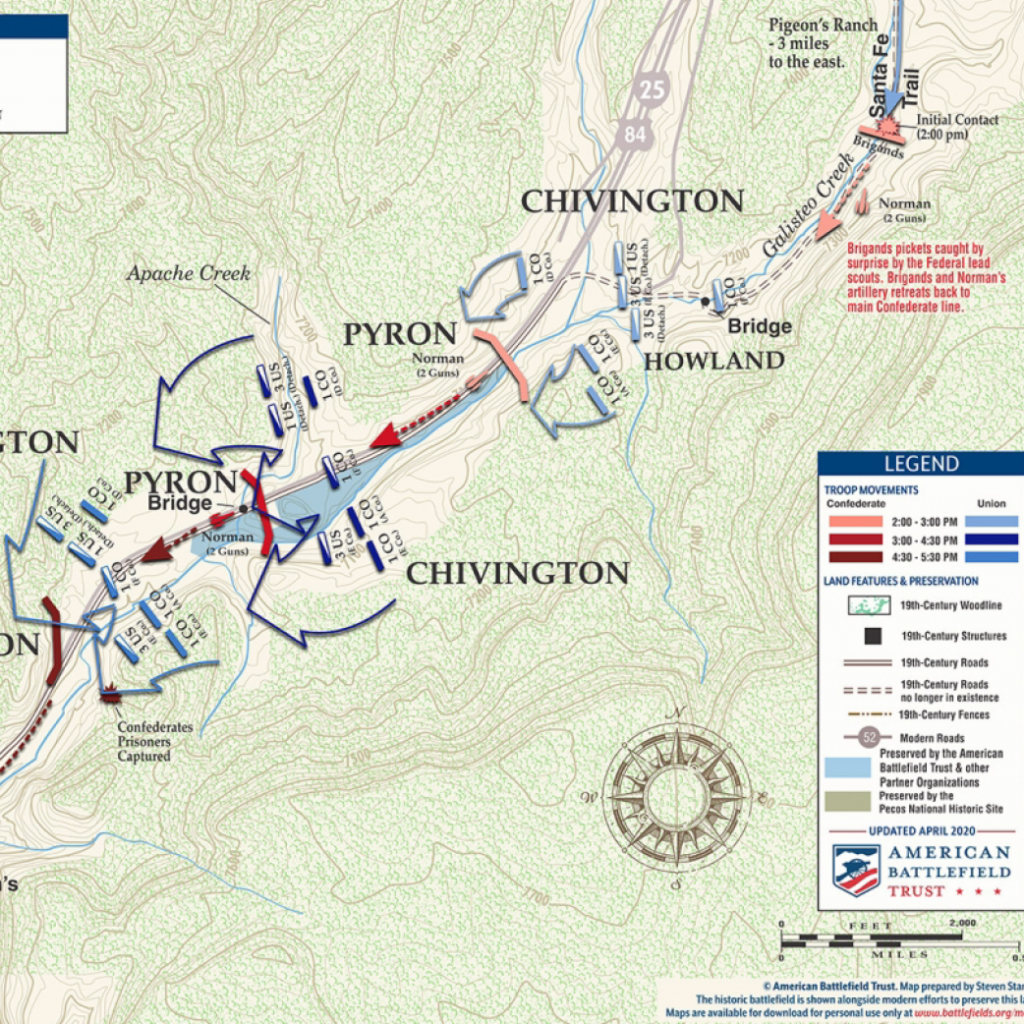

Glorieta, N.M.

March 26-28, 1862

March 26 – Apache Canyon

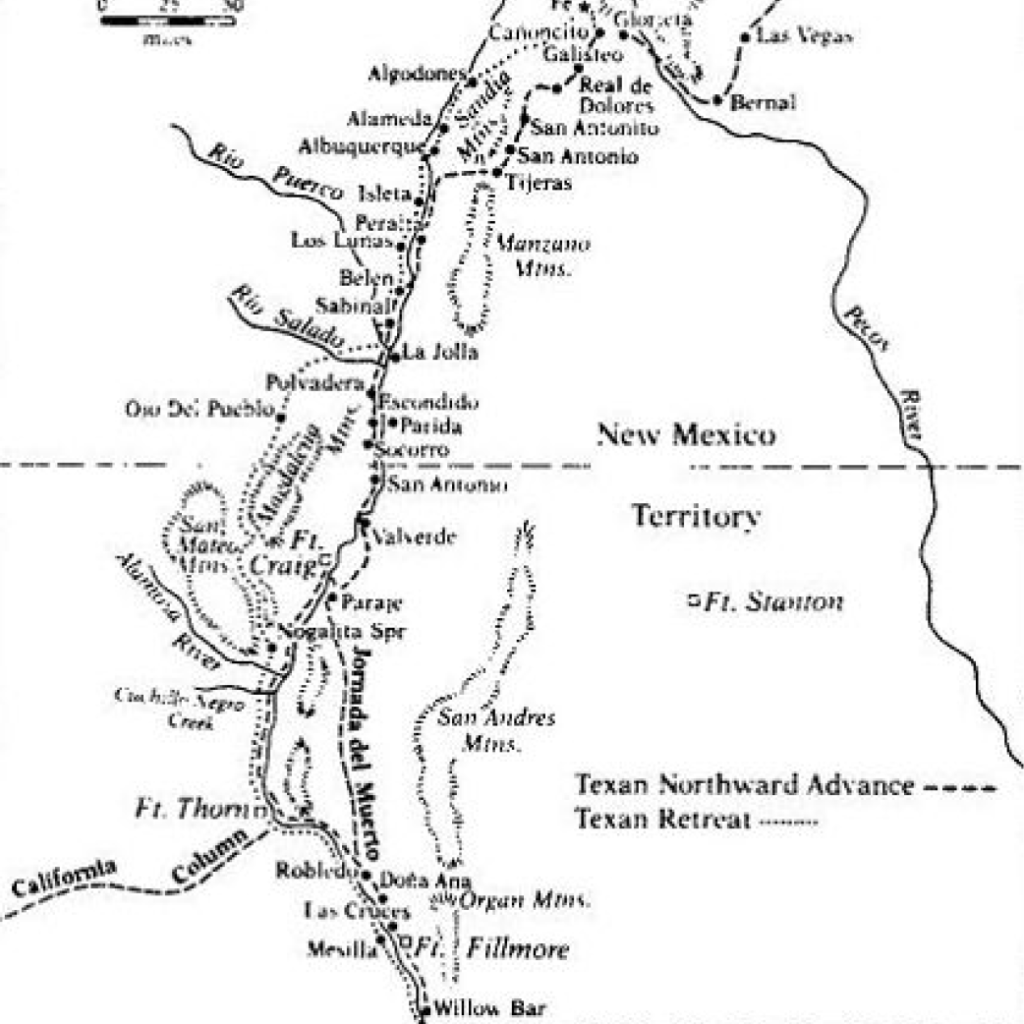

The Battle of Val Verde

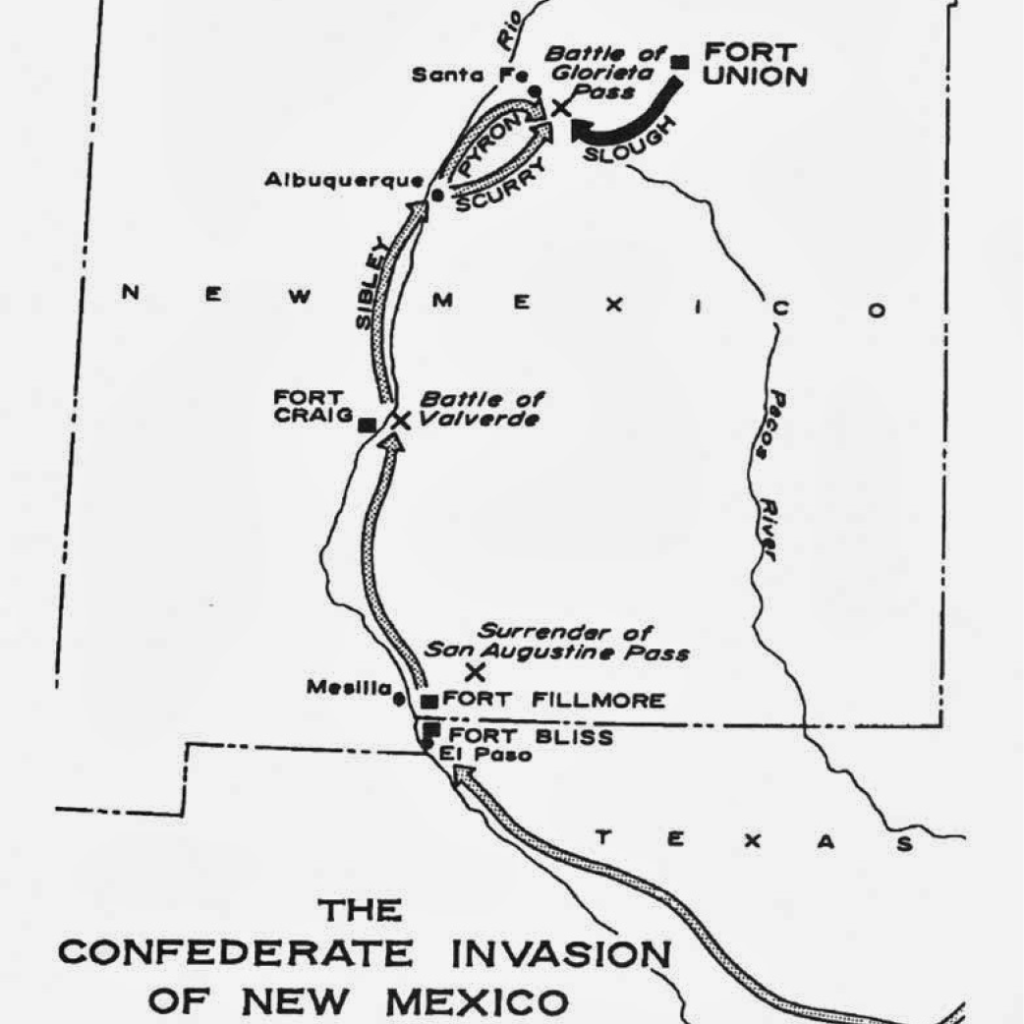

The Confederate Invasion of New Mexico 1862

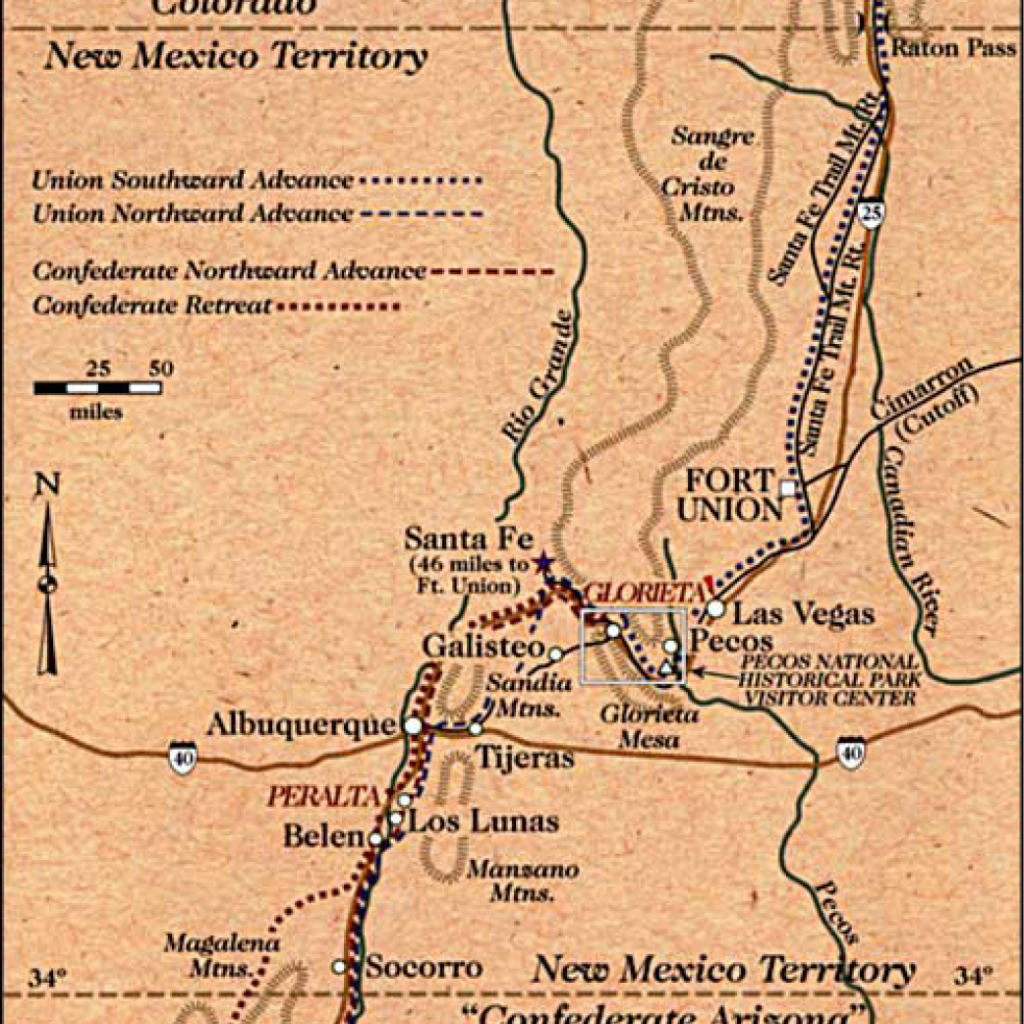

Union and Confederate Movements in the Southwest

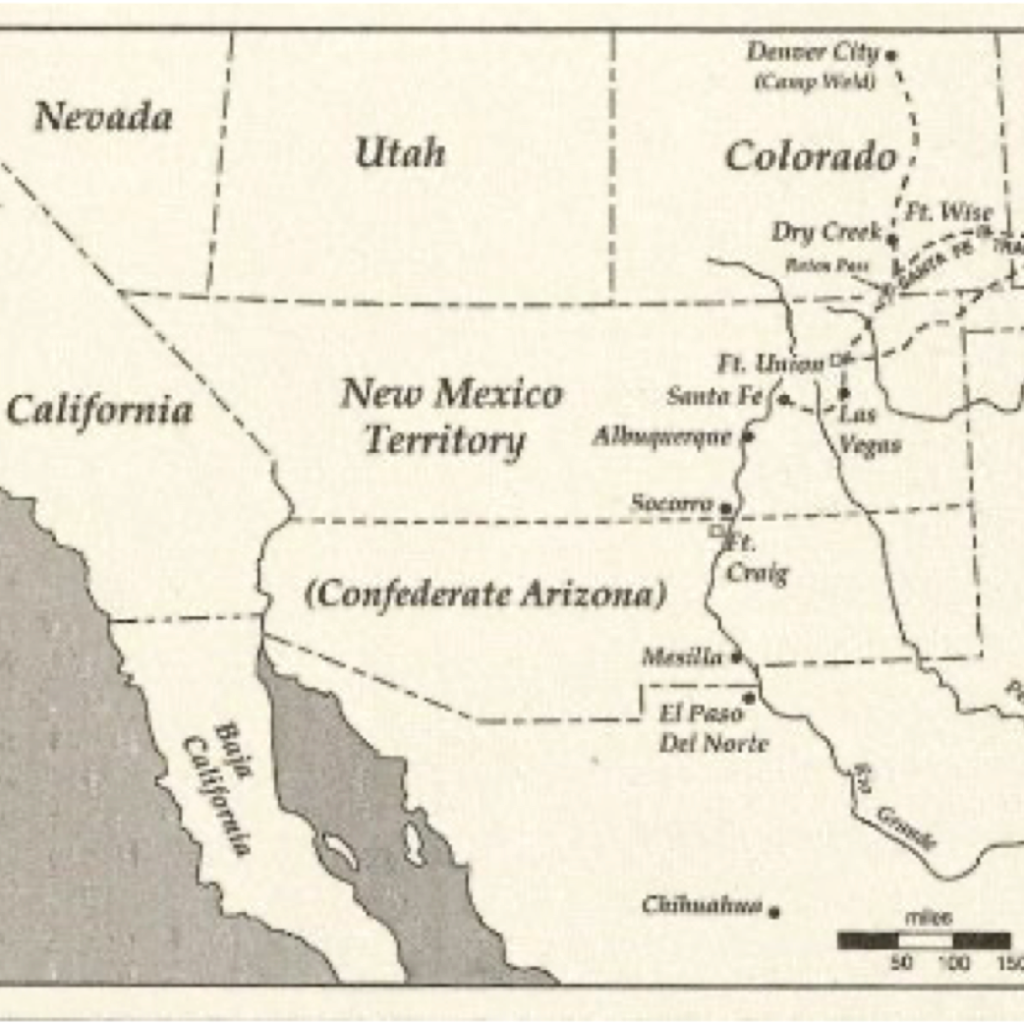

1862 New Mexico Campaign

Podcasts

Books

Videos

Other Resources

Fort Union and the Army in New Mexico During the Civil War

National Park Service

A GIS Study of Terrain Influences on the Battle of Glorieta, Pass, New Mexico

Anthony Schondel

New Mexico State University

Sibley’s New Mexico Campaign

Miles Mathews

Western Wyoming Community College

The Civil War in the Trans-Missippi Theater

Jeffery S. Prushhankin

Center of Military History, United States Army